Introduction

I participated in a Blended Intensive Program (BIP) titled “Quantifying Vulnerability to Natural Hazards in Changing Climate Patterns: New Perspectives and Methods”, hosted by the University of Bucharest. My motivation to join this program was to deepen my understanding of the risks and challenges posed by human actions on the environment, and to explore how climate change is increasing human vulnerability. The BIP explored and examined the interconnected relationships between susceptibility, hazard, impact, vulnerability, and resilience in a changing world.

The program ran from March 2025 to April 2025 and included two components: a virtual phase, where I attended a series of lectures, and a physical mobility phase held in Romania’s Vrancea seismic region. The online lectures covered a broad range of topics, including:

- Vulnerability in the age of the anthropocene

- State of the climate

- Sea level changes

- Social vulnerability in coastal environments

- Climatic and tectonic signals in landscape evolution

- Changing geohazards

- Dynamics of fragile coupled landscapes

- Increasing resilience

The physical component of the program consisted of field visits across the Subcarpathians and Carpathians, where we observed various landslide types, seismic risk factors, and community vulnerabilities in context - these visits complemented the theoretical knowledge from the lectures in real-world examples!

Physical mobility in Romania

Day 1 (April 7, 2025)

- We began the day in Bucharest, walking through central neighborhoods to observe how the city is managing seismic risk. Some buildings had been retrofitted to improve resilience, while others had clearly fallen into disrepair and would be at high risk of collapse in the event of another major earthquake like the one in 1977

- The contrast between upgraded and deteriorating structures highlighted issues of uneven risk reduction, as well as the influence of policy, investment, and maintenance gaps on urban vulnerability. Later in the day, we traveled by bus to Pătârlagele to begin the field visits in the Subcarpathian region!

Day 2 (April 8, 2025)

- In the Subcarpathians, we examined shallow landslides in the molasse terrain, where low-magnitude, high-frequency failures are common. Vegetation, especially moisture-loving species, helped identify unstable slopes. These polycyclic landslides, often reactivated, pose ongoing risks to agriculture and rural livelihoods

- At Oras Pătârlagele, we saw a complex landslide system shaped by mudflows and rotational slides. The visit highlighted the importance of long-term landslide inventories (30+ years) for climate-linked modeling, and how land-use change and property rights reform could support adaptation in high-risk zones

- In the Carpathians flysch environment in Siriu, we observed deep-seated landslides prone to plastic deformation during earthquakes, increasing rockslide risk. Narrow roads along unstable slopes and valley communities below are especially exposed to cascading hazards like landslides and flooding

- A locally built non-concrete dam served as an example of place-based adaptation to seismic threats. It underscored how local infrastructure decisions can play a key role in mitigating multi-hazard risks

Day 3 (April 9, 2025)

- In Nehoiu, we explored the Balta rockslide site, an example of earthquake-induced slope failure with scarps up to 90 meters high. The scale of displacement pointed to a high-magnitude trigger, likely seismic, supported by geological features like slickensides and fault-related deformation

- Using tools like dendrogeomorphology and lichen dating, we examined how the slope evolved over time. Evidence such as tilted trees and secondary scarps suggested ongoing instability and reactivation, making this a key site for understanding long-term hazard dynamics

- We also learned how lateral river erosion can trigger landslides that block valleys, creating natural dams that may later fail and generate dangerous outburst floods, highlighting the multihazard nature of this landscape

- Vulnerabilities in the area include modern housing placed on unstable slopes and narrow valley settlements directly in the path of potential mass movements. We saw how traditional, lightweight construction methods offer a locally adapted response to the instability

- Later in Chirlești, we visited a site affected by rainfall-triggered earthflows. The movement here was slow but destructive, with plastic and viscous soil behavior leading to damage to buildings, road blockages, and even indirect fatalities

- Poor drainage and infrastructure positioned at the base of unstable slopes made the community especially vulnerable. Adaptation strategies included improving drainage, reforesting slopes, and setting up early warning systems to reduce future risk

Day 4 (April 10, 2025)

- In Valea Lupului, we walked through a rural area where both social and physical vulnerabilities were visible. The condition and design of homes reflected the aging population—particularly older women—who are especially exposed due to limited access to social services

- We noted how solar panels offer a form of independence from state systems, but also introduce risks; in the event of failure, there’s no reliable backup since the local grid isn’t well connected

- Later, at the mud volcanoes (Vulcanii Noroioși) in Buzău, we discussed disaster risk reduction in protected areas. While there’s no direct exposure to communities at the site, the volatile landscape is vulnerable to wildfires and intense rainfall, which can affect infrastructure and limit tourism

- Lack of proper drainage systems and poor road access increase the risk for nearby areas. In surrounding ethnic minority communities, vulnerabilities are higher because homes are often on unstable slopes, and residents are usually last to receive emergency support

- Adaptation in these areas focuses on basic infrastructure improvements, especially roads and drainage, to reduce everyday risk and support long-term resilience

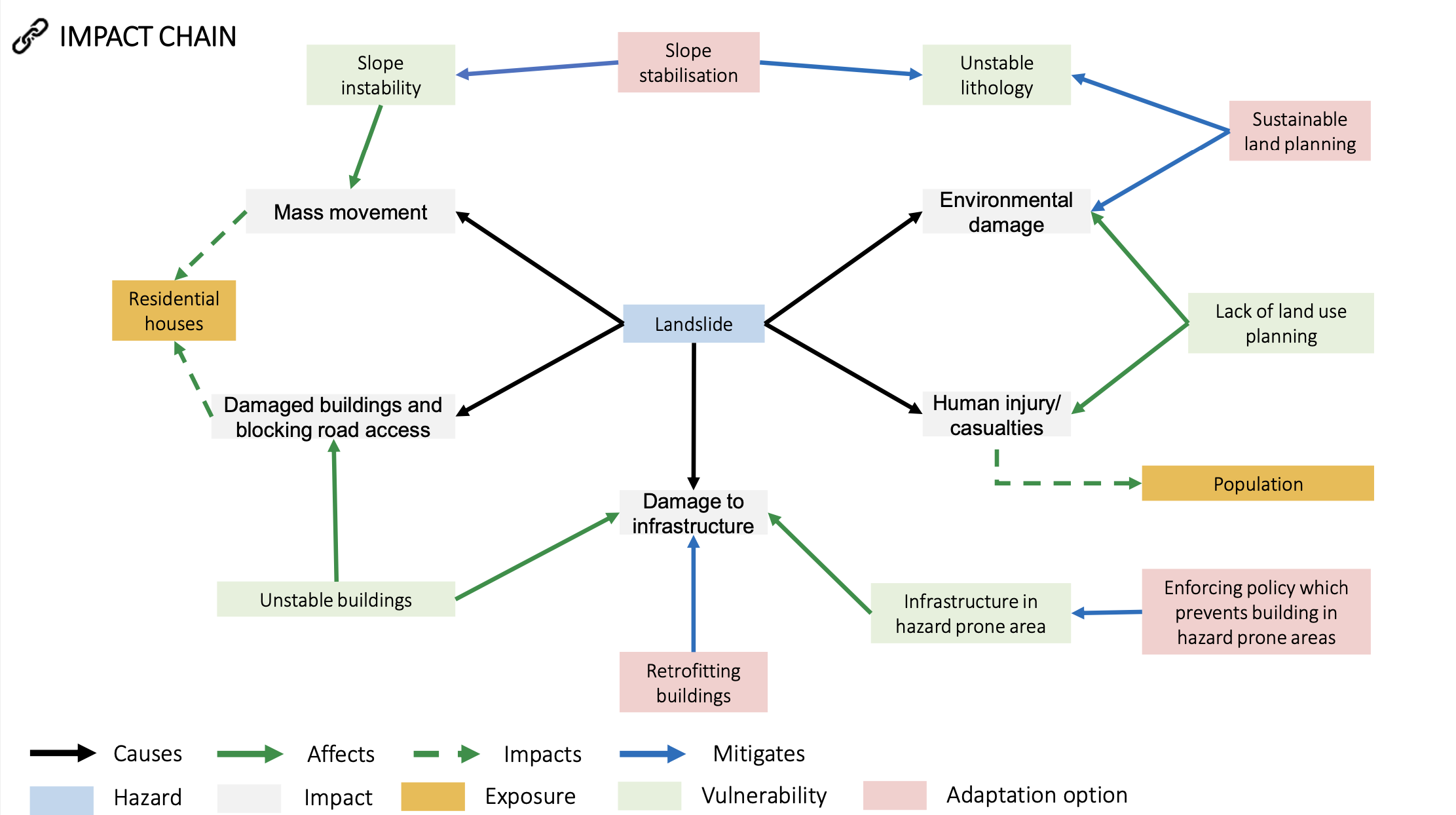

Impact chain

During our lab sessions, we worked on developing an impact chain as a way to better understand and organize the drivers and consequences of disasters. The exercise focused on how to structure, visualize, and use information to clarify both the what and the why of an event. My partner M. Fedyszyn and I created an impact chain on landslides, incorporating both classical and enhanced multi-hazard approaches. It helped us break down the complex interactions between physical triggers, exposed elements, vulnerabilities, and resulting impacts in a systemic, nice-to-see way:

Final thoughts

This BIP made it clear that addressing vulnerability is not just a technical or scientific task, but also evidently a deeply social one. To reduce disparities in exposure and impact, it’s essential to work across silos, by that I mean to say collaboration among scientists, policymakers, and local communities is key to developing responses that are both effective and equitable. Vulnerability often amplifies even small hazards, so avoiding new risk means building smarter, planning more inclusively, and making fairness a central principle.

This program was exactly the kind of experience I had hoped for in my Master’s studies. It gave me the opportunity to connect theory with practice and to observe firsthand how the physical processes shaping the Earth interact with people and ecosystems. I hope to carry these questions forward into my PhD studies, examining the intersections of geophysical hazards, climate change, and societal dynamics in shaping both risk and resilience in different contexts.

A big thank you to the University of Bucharest for putting together such a brilliant and thoughtful field trip, and to all the professors and peers I had the chance to learn from throughout!